Biography

Photo by Heinz O. Jurisch

Tadeusz Kantor (1915-1990) was once called “the best artist of the world from amongst Polish artists and the most Polish one from amongst artists of the world”. Already during his life, some considered him a genius, and others a master of mystification or a clever imitator only. Today, no one should doubt that this artist, who passed away in 1990, was one of the greatest creators of the art of the twentieth century. Even though it is difficult to explain what the phenomenon of his imagination was based upon. He was a versatile artist; a “total” one as he used to say, thus it is very risky to divide his output into individual “disciplines”. Being a painter, stage designer, poet, actor, and happener, he made a name for himself as a man of theatre, but even in the domain of it he remained first of all a painter who thought with images and used actors and props instead of paints.

Kantor’s greatest achievement was The Cricot 2 Theatre. Its performances, beginning with The Dead Class (1975), attained the level of masterpiece. The unusual formula of his Theatre of Death consisted in creating artistic illustration for mechanisms of memory. Sequences of unreal pictures, snatches of memories, obtrusively returning scenes, and absurd situations: everybody knows this from his own experience. And all of us are confused in a similar way: series of painful resentments, daring longings, remembered fragments of sentences, comical scraps of the past. We are physical, and it appears that our memory and imagination are also physical. We do not exist without form; we think and even feel with images. And Kantor could show it on the stage. He created an unusually suggestive space in which the living and the dead have been mixed, where the shyest desires and most cruel experiences, i.e. war, love and crime, fear, passion and hatred have been revealed. On faded photographs of his family album, the personal biography intertwined with history, where national myths and private obsessions returned with tiresome echoes, like in the distorting mirror.

Kantor was an inspired creator who treated art very seriously. Balladyna and The Return of Odysseus, the pieces prepared and performed during the wartime, marked the actual start of his artistic way. Creating an avant-garde theatre in the climate of threat and conspiracy, he revealed his real hierarchy of values, i.e. the conviction that the independence of an artist and the freedom of art are possible in all circumstances. Under the Communist rule it meant first of all the communication with the world and maintaining links between Polish and European art. As an avant-garde artist, Kantor needed to be au courant, and therefore he used to bring the newest art recipes from the West. In that time, the eager pursuit of modernity was coming not from snobbery, but rather from the need to break the isolation of civilisation and to join the artistic life of Europe. In a cutting way, critics called Kantor “a travelling salesman of novelties”. Instead, he had a sense of mission. He treated tracking and transplanting new art trends as an apostolic mission, duty and privilege. He was the first one who brought informel, conceptualism and happening to Poland. He used to say whole-heartedly, “What’s important, it’s not the influence, but the cause!” He was right, and this was why in his art there is no boredom typical of various kinds of avant-garde. He has always replied to somebody else’s questions with his own and unique answers. In his own way, he was sovereign both towards contemporary art and tradition. He has added contemporaneous and unceremonious commentary to the greatest, i.e. Rembrandt, Velazquez, and Goya. Since the very beginning, he had the courage to take up the dispute with creation of the Polish bards: Słowacki, Witkacy, Wyspiański, Veit Stoss. His art can be described as a lesson of creative dialogue with the past, as an attempt to join in national tradition, and an original avant-garde correction of repeatedly asked questions.

Photo by Daniel Simpson

Even though he did not like the term, Kantor used to say that a good picture should be “directed”. “When somebody says that I am a director, I don’t agree,” he repeated, “When he calls me a painter, I agree, because it’s an old term of enormous tradition, but the director? Only about two hundred years…” Painting was for him an actual laboratory of ideas, a private scene of dialogue with tradition, the avant-garde, and the whole world. It is worth looking at the pictures that explain successive steps of Kantor’s artistic path. In them he comes into view sometimes more clearly than on the stage. His “metaphoric pictures” painted in the forties, full of tangled and deformed figures, were his way of getting over the war and post-war traumas. These pictures explained psychical entanglements by means of the language of spatial tensions. His abstract and showy informel canvas (“dispelled with the wind of chance”) are, in turn, the record of impetuous gesture, manifestation of freedom, but also the germ of drama. As Kantor remembered: “It was a secretion of my INSIDE where passions, desires, despair and delight, regrets of the past and all its longings were whirling along with the memory of everything and with the thought that fluttered as a bird during a storm”.

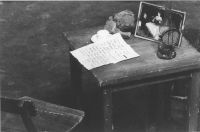

When eventually the artist became bored with abstract art and when returning to the illusion of painting seemed to be impossible, he used a trick, including real materials and objects into pictures. He has concealed the reality under wrappers; hence his famous emballages. Since then he has made art from everything. As he used to say, “Metaphysics must have its own physics”. The most common garbage, all the “reality of the lowest rank”, bags, umbrellas, notes, crumpled rags and pieces of paper, all this could become that kind of physics. Several times, the artist seemed to lose belief in the sense of imaging. He directed all his energy to transgress conventions: hence his numerous actions, happenings and conceptual ideas. The series of The Vicinity of Zero and Everything’s Hanging by a Slender Thread sounded as the obituary of painting. But in the end Kantor always appeared to be true and actual painter who often returned to the easel. At the end of his life he painted surprisingly traditional and sentimental pictures having the virtue of personal confession.

Photo by Jacquie Bablet

Fervour and unconditional belief in art were the most important features of his attitude. Kantor had the charisma of a leader, a prophet; he could gather other creators around him and encourage them with enthusiasm. He played great role in this field within Polish art. Wherever he appeared – in the underground theatre, in the front of The Cracow Group at the Krzysztofory Gallery, at Warsaw’s Foksal Gallery, at the Academy of Hamburg, during theatre training in Florence or Milan, Italy or in Avignon, France – his fascinating aggressive personality always won over faithful advocates. He was a true visionary; he could inspire creative ferment and arouse the creativity of listeners. The co-founder of The Cracow Group, Janina Kraupe recalls: “Art was an extraordinary real thing for him, something he actually lived with. We could talk about truly important things with him. His generation of artists believed that art was the way through which the truth could have been sought. When practising painting and theatre, Kantor has been meditating, in effect, over the sense of life”.

Within the landscape of Polish art, Kantor is an important symbol, a kind of emblem of the twentieth century. On successive stages of his artistic biography we can learn the history of contemporary art, its discoveries and illusions, its investigations and ambitions. Kantor’s creation reveals the nature of the ethic lesson of actual avant-garde: faith in incessant creation, continuous anxiety of risk, and transcending yourself. When we choose only one tested convention, we are threatened with fossilisation and artistic opportunism. In spite of it, and as if against the pressure of innovation, Kantor aimed at the Great Synthesis throughout his life. He reached it in the performances of his Theatre of Death. When we remember it, every earlier step, even apparently insignificant or not satisfactory, becomes important as a successive level on the way to self-realisation. They show Kantor’s way of thinking, his way of development, and the sources he exploited. He had to try various ways, to eliminate cul-de-sacs, to check the capacity of his own imagination. From the perspective of The Dead Class or Today Is My Birthday, the artist’s capricious changeability appears to be a consistent and fully conscious attitude.

fot. FLORE/Wolland

Passing the viewer is the drama of the whole art of the twentieth century. The bigger ambition artists had in their desire to win the world and make it fall on the knees, the more painful appeared the hermetic character of their work and the less necessary such work seemed to be. Trying to be a common language, art has often become silent. The importance of Kantor consists in the fact that he managed to overcome this phenomenon. Starting with elitist art, he managed to reach different people all over the world at the end of his life. This evolution is an example of the beautiful process of growing of the artist who could give up current fashions. He ceased to look nervously around the world, came back home, and started to seek in himself, in his childhood memories, in the symbols of Polish Romantic tradition. And, paradoxically, just the “provincialism” and private mythologies appeared to be the right path towards the world. It was the journey far into the artist’s memory and imagination instead of any feverish or revolutionary pursuit “forward”.

Kantor inscribed the history of his personal struggle for his artistic soul and the rapture of viewers into his whole work, i.e. into painting, drawing, and theatre. The twentieth century art was torn between two extremities: the rational and orderly vision of the utopia of pure form preached by constructivists and the literary tradition of symbolism with its longing for art full of contents and emotions. The integration of these two trends by means of exposing symbols and emotions to the iron discipline of form is one of the greatest Kantor’s achievements. He used to say, “I want them to see and cry”. In a mysterious way he managed to hypnotise the viewers. People cried during his spectacles at any latitude, in Japan, Argentina and France. Neither knowing Polish traditions or language nor reading biography or the author’s commentaries, they gave in to emotions and cried. A small town in the province of Galicja, reconstructed from the pieces of memory and faded photographs, became the centre of the world. This was the shocking portrait of the past century with its cruelty and heroism, with the tragedy of the Holocaust, and the drama of subjugation. The age of war and death, daring utopias and artistic revolutions found an unusual record in Kantor’s creation. His art appeared to be a testimony, both personal and universal. This is the privilege of the greatest.

Prepared by: Krystyna Czerni

Translated by: Elżbieta Chrzanowska-Kluczewska