Mitoraj versus Kantor

Tadeusz Kantor and Igor Mitoraj are two outstanding Polish artists of the 20th century who achieved great success on the international arena, establishing lasting canons of art and constructing an autonomous language of expression.

Their relationship has never been the subject of detailed research; at first viewing, their art is not overtly related. Only a detailed reading of the artists’ biographies and an in-depth analysis of their works reveals an array of common features, similar determinants for artistic creation and an identical conception of art.

Kantor was a key turning point in Mitoraj’s artistic evolution. Mitoraj was Kantor’s most outstanding student, whose talent and ability to gain worldwide acclaim were immediately recognized by the Master.

Academy

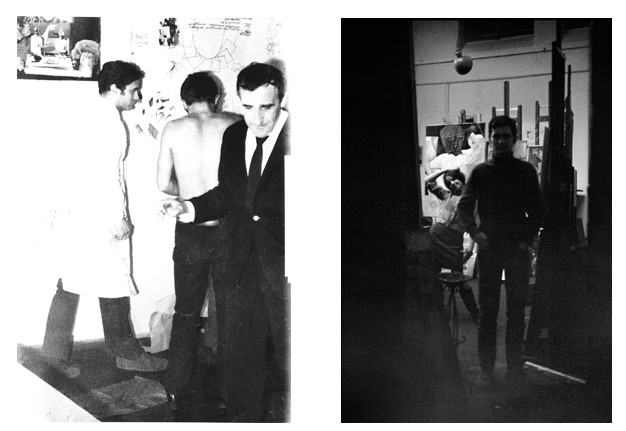

Tadeusz Kantor meets with his students in the artist’s studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (1967/1968). From left: Igor Mitoraj, Stanisław Szczepański, Tadeusz Kantor. Photographer unknown

Tadeusz Kantor meets with his students in the artist’s studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (1967). Facing front: Igor Mitoraj. Photo by Aleksander Mitka

The artists’ paths crossed in 1966 in Kraków. After finishing the Secondary School of Fine Arts in Bielsko-Biała, Mitoraj entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, where in the academic year 1967-1968 he was a student of Kantor, who was already regarded as an outstanding figure in the Kraków community and served as Chair of the Third Department of Drawing and Painting at the Faculty of Painting and Graphic Arts.[1]

Mitoraj studied with Kantor for only a year, but it was a crucial period for the formation of his artistic consciousness. Kantor’s legendary studio was a kind of experiment with art, people, painting and artistic matter. Mitoraj said in an interview: “Kantor had such passion in him, such fire, that he set our brains ablaze for art. … I’d do anything to be in Kantor’s Studio. I would give my hand to be at his place and with him. I don’t know why. It was this personal magnetism of his that I wanted and needed to be with him. He did not teach us art, but taught us how to look at art, how to open yourself to art, how to find yourself.”[2] Mitoraj initially leaned toward painting, and did not think about sculpture. “Under Kantor’s direction, the artist paints, draws, makes collages from random objects, but also prepares imprints of bodies, inserting them into his compositions. He was fascinated by Kantor’s experiment inspired by the French artist Yves Klein’s “Anthropometries”, ultramarine[3] monochromes made by imprinting models’ naked bodies, covered in paint, directly on canvases”. The experiment carried out by Mitoraj in the master’s studio influenced the later monochromatic nature of Mitoraj’s sculptures and his predilection for using blue. The artist recalled: “Klein was a shocking discovery to me, his creation of a blue hole in a blue sky left traces in the blue patinas of my sculptures.”[4] Kantor managed to instil in Mitoraj a fascination for the body in space, the body as matter, and finally the body as a central point of reference and also a work tool. Man, corporeality and changes in the body are the main axis of interest for both artists.

In the end Mitoraj did not finish his studies, leaving in 1968 for Paris, where his career quickly gained momentum. The artist’s decision was influenced in no small part by the words of his master, who said: “There is no place for you here. You have to leave, you have to get a foothold in one of the art capitals if you want to secure your future. You have a chance, after all, you don’t want to remain anonymous.”[5] Even a few years later, Kantor confirmed Mitoraj in his belief by sending him a New Year’s card to Paris in 1972: “You should stay in Paris for as long as you can stand it. Don’t worry about the Academy – it doesn’t matter!”[6]. Recalling this message in an interview, Mitoraj said: “Because, on the one hand, we are prepared for tradition, but on the other hand, it is necessary to break away from the world of tradition and go out in the world as unconsciously as possible. To throw yourself into those waves that are crashing all over the world. And Kantor gave me a very good lesson, to disconnect from the system, the ASP, etc. The Academy was a great place to meet my peers, to exchange views and ideas, but that’s not enough. You can’t get stuck in this. You must act outside the Academy. I got a lot more out of meetings with Kantor outside the ASP. It was very important for me at the age of 22. Those were long discussions in Krzysztofory at night, very personal, full of smoke and alcohol, but they gave me a lot for many years later.”[7] Kantor thus not only moulded his thinking about art, but also set his student on a specific path. He wanted Mitoraj to experience the same things he did during his Paris scholarship in 1946, which, through a wealth of inspirations, new experiences and opportunities, was a catalyst for change in Kantor’s work and one of the greatest turns in his artistic development. Kantor’s faith in his talent was extremely important to Mitoraj at the beginning of his artistic journey as a source of support and courage to change. As an already established artist, he recalled that Kantor once told him: “I can see in your eyes that you’re going to be somebody. I will never forget it.”[8]

Sources indicate that they saw each other again only once, in 1975 in Paris. The sculptor recalls that Kantor was busy, somewhat depressed, but ready to laugh at the sight of Mitoraj: “The theorist of the “theatre of death” exorcised death with laughter, defended himself with irony and self-irony.”[9]

Exhibition “Tadeusz Kantor i Akademia” (Tadeusz Kantor and the Academy), Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (10 December-15 December 2000). Photographer unknown

Exhibition “Tadeusz Kantor i Akademia” (Tadeusz Kantor and the Academy), Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków (10 December-15 December 2000). Photographer unknownThe context of the Academy of Fine Arts returned in the winter of 2000 in an exhibition entitled “Tadeusz Kantor i Akademia” (Tadeusz Kantor and the Academy). Held in the Academy’ s building in Kraków, the show juxtaposed selected paintings by Kantor with works by his students. Next to the master’s paintings were two busts by Mitoraj and his sketches. A common feature of this dialogue, foreshadowing further connotations between the artists, were the images of deconstructed human figures: the geometrized anthropoids in Kantor’s canvases and the eyeless, bandaged faces in Mitoraj’s sculptures. What Kantor tried to make his students aware of, and what he advocated throughout his work, was the beauty and inner tension of a work of art separated from classical notions of harmony and aesthetic canons, but inherent in imperfection, flaw and otherness. Many years later, it was clearly reflected in Mitoraj’s artistic premises.

Similarity of the Fates

What also brings the artists together is the similarity of their fates. They both came from the provinces. Mitoraj’s childhood and youth were associated with Grojec, a village near Oświęcim; Kantor lived in the village of Wielopole Skrzyńskie near Rzeszów until the age of six.

Both artists grew up without a father. As a child, Igor would go out on the road to wait for his father returning from his postwar wanderings. “When I was five or six, I kept going out on the road, without even thinking about it, and waited… I hoped that one day my father would appear on the road… It seemed to me that it could be any approaching man.”[10] However, that officer of the Foreign Legion never returned to his family and settled in Saint Denis near Paris. This was one of the reasons why Mitoraj wanted to go to France so much. “My greatest desire at that time, almost an imperative, was to meet my father.”[11] But when he stood at his door in the 1970s, he changed his mind at the last moment: “Maybe I subconsciously chose the mystery that had shrouded my father forever. Maybe because unfulfilled dreams are the most beautiful. Maybe I was dreaming a dream about a person who did not exist … I never even wanted to know if he was still alive or dead. For me, he was already dead. It was not his fault that he disappeared from our lives so completely; I believe history is to blame for that.”[12] But as soon as he could – the opportunity presented itself when he had to obtain the documents necessary to stay in France – he changed his first name from Jerzy, given to him after his father, to Igor.

Kantor’s father fought in the Polish Legions during World War I. Born shortly after the outbreak of war, the artist barely remembered his father – in a soldier’s uniform, with a rifle and a suitcase. After the fighting ended, Marian Kantor also did not return to his family, and in 1942 was arrested by the Germans and deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, where he was shot a month later. Both artists made the figure of the father, or rather his absence, an important motif in their work, although each worked through the issue in a slightly different way. Kantor did this in the autobiographical productions of the Cricot 2 Theatre. In “Wielopole, Wielopole” (1980), the father is the spectre of a dead soldier; in the autobiographical “I Shall Never Return” (1988), Kantor creates a mannequin of the Father and reconstructs his execution on the stage to the sounds of an announcement from the Death Camp. Mitoraj, on the other hand, equates the absent father with mystery. According to scholars of his work – the father figure appears in sculptures with bandaged heads, which symbolize being locked in a never-solved mystery. The search for a father is combined in the artist’s work with the search for himself: “The most important thing is to search for yourself, or even your reflection. After all, an artist is a narcissist from birth. My mirror was the search for my father, for an obscure reflection of my soul. […] I must add that the search had a big impact on the male symbolism used by me.”[13]

The empty place left by the father is occupied in both biographies by the mother, who is at the centre of the artists’ lives. Kantor made multiple use of the mother figure in his performances. He wanted to be close to his mother even after death, which is why he built a common tomb for her and himself. Mitoraj had great love and respect for his mother. He wrote about his childhood: “I was still small, but we had suffered a lot, beyond imagination. For this reason alone we were so attached, so close to each other.”[14] The mothers – Helena and Zofia – were a true support for their sons, believed in their artistic vocation to the every end, never doubting their talent.

Their personal, war-related experiences were another foundation for the artist’s closeness. Although Mitoraj was born in 1944, the place where he was born and the story of his parents would make World War II an important part of his biography; he lived in the shadow of his mother’s memories of the war.

Forty kilometres from Grojec loom the chimneys of Auschwitz. Thus, the proximity to the site of the extermination of the Jewish people, Poles and other nations had a tremendous impact on the young artist, especially since the atrocities committed during World War II were often and openly discussed in the 1950s. The image of the twisted, mutilated bodies of people gassed in the chambers was permanently etched in Mitoraj’s consciousness and would be reflected in his works as damaged torsos. In the film “Więzy”, the artists confessed: “In Grojec, one felt the presence of Auschwitz, which to some extent cast a shadow over my life. I myself was born in connection with the existence of Auschwitz.”[15]

While World War I was a vague childhood memory for Kantor, World War II left a lasting mark on all of his work. During the Nazi occupation of Kraków, the performances of the Underground Independent Theatre were staged by Kantor and the artists gathered around him in dangerous and lonely conditions, surreptitiously, against prohibitions, under penalty of death. Making art in a time of destruction was forever marked with rebellion and protest against the mechanisms that govern history. Hence the deformation and disruption of form, the aesthetics of remnants, wreckage and repetition typical of Kantor’s paintings and theatrical works. What was doomed to degeneration and abandonment became a battlefield for him. It was apparent both in the material sphere, as with the idea of a “poor object or ‘reality of the lowest rank”, and in the mental sphere – in being on the edge, in between, making use of understatement, anxiety, contradiction and aura. Events in 20th-century history, such as the two world wars, the Holocaust, totalitarianism, mass movements and ideologies, sociocultural changes, displacements and migrations underpinned Kantor’s strong emphasis on the individual human conditions as opposed to massification, focus on his own biography and inclusion of private themes in art.

Finally, another common feature of the two artists’ biographies is that both were more highly regarded abroad than in Poland. Kantor’s performances and Mitoraj’s sculptures were regarded as brilliant in the West, having a significant impact on contemporary art, while in Poland they remained misunderstood and underestimated for many years to come.

Melancholy

Exhibition of late self-portrait and painting series by Tadeusz Kantor, “Tadeusz Kantor. Cholernie spadam!” (Tadeusz Kantor: I’m Goddamn Falling!), Cricoteka, Kraków (2015). Photo by Zbigniew Prokop, Krzysztof Kućma / Creator s.c.

Exhibition of late self-portrait and painting series by Tadeusz Kantor, “Tadeusz Kantor. Cholernie spadam!” (Tadeusz Kantor: I’m Goddamn Falling!), Cricoteka, Kraków (2015). Photo by Zbigniew Prokop, Krzysztof Kućma / Creator s.c.What Kantor and Mitoraj share as artists is not only their interest in the human being, expressed as a focus on the motif of corporeality, but also the above-mentioned deformation of the human figure. As Kantor wrote : “The time of war and the time of the “lords of the world” made me lose my trust in the old image, which had been perfectly formed.”[16] From the 1940s on the human figure was the main protagonist of his paintings, drawings, later also sculptures, but it was constantly subjected to decomposition: broken, fragmentized, enlarged with objects, hybridized. Mitoraj, on the other hand, operated with fragments of the human body. This fragmentariness had its origins in the condition of ancient sculptures, which have survived to the present day, but without limbs or heads. Incomplete bodies are a symbol of the disharmony that came with the disintegration of ancient civilizations, and at the same time a hallmark of postmodernist art, based on a constant dialogue between modernity and tradition. Processing the Iron Age and then the Lead Age with its ruthless cruelty, the two artists confirm the modern intellectual disbelief in wholeness, which is a form of self-doubt and doubt in humanity. Mitoraj and Kantor also share a subtle melancholy. It is evident in the fragmentation, cracking and patina of the former’s sculptures, and in Kantor’s use of worn objects, of what is marginalized, exhausted, moving on the fringes of reality, carrying the past. This quality is rooted not only in the artists’ personal experiences , their fears and obsessions, but also in the trauma of the experience of 20th-century totalitarianism, tragedy, premonition of disaster and genocide.

Melancholy in Kantor’s work came fully to the fore in the Cricot 2 Theatre’s production of “The Dead Class” (1975) in the figure of death as reality and in the game of appearances. “Everything that is on stage, what we see and hear, is less important than what is not there. Its primary purpose is to build in us, the audience, the conviction that something is missing – and that this is, in fact, the point. … We are beginning to feel the growing suction of the emptiness within us.”[17] This “in-between” zone, characteristic of the artist’s work, is one of the basic melancholic states: between memory and oblivion, between the illusion of presence and non-existence, between the living and the dead. The mannequins used by Kantor in the theatre – doubles of the human image – make up an image that is shattered, fragmented, like the cracked surface of a mirror. Kantor discovers for himself some hitherto unnoticed truth about man in this split, and at the same time finds in it the possibility of expressing this “new” liminal human condition in his art. Arguably, the double is a metaphorical figure of memory, a reference to the realm of death, an expression of the search for oneself and the ever-repeated attempt to construct and deconstruct one’s identity – constantly shattered, scattered and confronted with an other (a stranger), looking alike or not, in whom one must recognize oneself.

Exhibition of selected sculptures by Igor Mitoraj at the archaeological site, Pompeii (2016). Photo by PAP

Exhibition of selected sculptures by Igor Mitoraj at the archaeological site, Pompeii (2016). Photo by PAPCostanzo Costantini notes: “Mitoraj models his sculptures to the last detail, even though they are shattered, broken and flawed; he fully models every fragment – hand, foot, eye, sex, wing, torso – because this fragmentation reflects the human condition and social situation today: the divided self, the split personality, the violence inflicted by people on others and themselves, the deep conflicts between consciousness and the unconscious, all the alarmingly pulsating self-destruction that can be sensed in our world. Mitoraj does not hesitate to show that beauty is able to survive any mutilation, any attempt to destroy it. […] Mitoraj’s sculptures fully reflect the time we live in: time broken into fragments, just as the human being in his work is broken into fragments. The artist conveys a ‘frenzied’ time, in which the past invades the future and the future invades the past, involving and shattering the present in the process.”[18] Mitoraj’s sculptures are simultaneously wholes and fragments, as is the case with Kantor’s stage strategies. The blurring and fusing also manifest themselves in the fact that Mitoraj engages in a dialogue with his own art, citing his sculptures, reduced or enlarged in scale, incomplete or pared down to a fragment, in other works. None of these sculptures is a closed composition. On the contrary, they transform before our eyes. In Kantor, a similar device would be his consistent construction of a map of references drown from his personal and artistic biography, which pulsate in all of the art forms he worked in.

In Kantor’s view, “The war turned the world into a “tabula rasa”. The world was one step closer to death – and metaphorically – to poetry.’[19] This perception seems to be common to both artists, and its consequence is a kinship of metaphorical-symbolic thinking, of pictorial expression based on the iconic use of the self, consisting in a kind of exhibitionism, albeit delicate and sublime.[20] This melancholy rooted in specific existential conditions can be placed in a broader context – of the whole experience of postmodernism, identified by some cultural critics as a kind of macronostalgia.[21]

Packaging

Exhibition of selected sculptures by Igor Mitoraj at the archaeological site, Pompeii (2016). Photo by PAP

Exhibition of selected sculptures by Igor Mitoraj at the archaeological site, Pompeii (2016). Photo by PAPSimilar content is inscribed in Mitoraj’s bandaged heads and his torsos and waists bound with string. The sculptor declares: “To me, the bandages symbolize a protection against reality which, from an early age, seemed deeply hostile to me. I see them as a symbol of the belief that you must nevertheless go on living. And besides, this is another component of my Polish consciousness, that tormented, wounded and closed consciousness. It’s a visual expression of that consciousness.”[22] The bandages certainly protect the sculptures from the cruel world, while making them more mysterious and intriguing.

“Bendato” (bandaged) or “addormentato” (dormant) are thus an expression of the separation of the self from reality and are very close to Kantor’s emballages, which the artist used when Mitoraj was his student.[23] “Emballage” means “packaging” in French. In his paintings and performances, Kantor packaged what was most precious, what needed to be saved from oblivion, protected from destruction, what had to be hidden from others. After his experiments with the matter of objects, the greatest accumulation is the packaging of the human figure in the artist’s happenings such as “The Great Emballage” (Basel, 1966), where the human body is meticulously wrapped with rolls of toilet paper. Later, Kantor took up the task of recording the intimate process of recalling his mother in the installation “Portrait of My Mother” (1976), where he condensed his longing for her, as it were, filling the absence left by her death in the realm of art. In both artists, then, we are dealing with inexplicable secrecy, mystery and ephemerality inherent in what is covered, which the viewer intuits but is unable to define clearly.

Packaging a human figure in the happening “Cricotage”, Kawiarnia Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych (Café of the Society of Friends of Fine Arts) in Warsaw (10 December 1965). Photo by Jerzy Borowski

Packaging a human figure in the happening “Cricotage”, Kawiarnia Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Sztuk Pięknych (Café of the Society of Friends of Fine Arts) in Warsaw (10 December 1965). Photo by Jerzy BorowskiBoth in Mitoraj’s bandaged heads and in Kantor’s visual concepts, the mask plays an interesting role. Both artists return to the function of the mask known from its ritual-ancient origins, when it was associated with the actor, defining the meaning of his role. At the same time, they draw on contemporary psychological meanings, intensifying as well as individualizing the expressive values of the mask. By covering faces with bandages, Mitoraj cuts the subject off from the outside world. That which is covered becomes a semantic indicator of what is on top. In the works that use this gesture, as in the giant masks with empty eye sockets – behind which there is no one looking – the pervasive impression is that of one, final mask. It is the mask that triumphs in death over the many that come and go on the face.[24] In Kantor’s theatre, the face itself takes on the function of a mask – the artist urged the actors to be constantly themselves (and thus keep their own face), while simultaneously adopting a mask – painted with strong stage makeup, turning the face into a frozen expression. In the work of both artists, the mask points to association with death on the one hand, and on the other, to the dark, usually hidden side of human consciousness, which sometimes carries an “other”, an alter ego or double working through traumas and fears. This doppelgänger, shattering the smooth (familiar) image of identity, like a mask that multiplies reflections of “I”, is in fact one of the figures of melancholy. As Hans Belting writes: “The expressive achievement of the living face lies as much in its ability to show and proclaim as in its ability to conceal and deceive.”[25] Mitoraj and Kantor, balancing between the face and the mask that replace each other (mask on the face and face on the body), do not build opposition to those concepts, but a peculiar relationship between nature and culture, which is a syndrome of 20th and 21st century art, oscillating between the face as expression and the face as structure or even its simulation.

Autobiographism

Another common feature is the autobiographism of both artists’ work and the concept of integrating life and work. While Mitoraj described the creation of a complete figural sculpture as a kind of finish line in his life, Kantor first turned to figuration in his late period. The decomposed human figure is replaced in his paintings and theatre by the self-portrait, through which the artist talks about his condition at the end of his life and takes stock of it guided by a premonition of impending death. Kantor created stage roles for himself, and Mitoraj admitted in an interview that he had been a model for his sculptures on several occasions.[26] The artists processed numerous themes from their biographies in their works, such as the absence of their fathers and their attempts to symbolically keep their mothers. In his sculptures, Mitoraj used the motif of small torsos placed in deep rectangular openings, resembling frames of celluloid tape. They were a reminiscence of his old, untapped fascination with film, as was his desire to frame, to make one aspect of his sculpture similar to the freeze frame.[27]

Both artists devoted their entire lives to the creative imperative: Kantor persistently made all surrounding reality the material of his creation, Mitoraj fused the creative act with his everyday life, calling this state the “loneliness of the long-distance runner.”[28] The sculptor said: “[…] Art is also a search for the self. It is a kind of self-analysis, of psychoanalytic therapy. […] For me, the ideal solution would be to disappear, to be physically integrated with the sculpture.”[29] Kantor, after ten years of exploiting biographical themes and personal references in his theatre, decided to incorporate death into his work in his last performance, “Today Is My Birthday” (1991): first he designed his funeral on stage, and four days later he died. Art and life merged into one.

The Final Work

Both Kantor and Mitoraj are total artists, uncompromising and stubborn. Above all, they are versatile; fusing life and art into one like an amalgam. They have one more thing in common, what can be termed their final “work”: They designed spaces in their beloved cities in order to disseminate their work to future generations of audiences and researchers. The Atelier Mitoraj founded by the artist himself in Pietrasanta is dedicated to protecting, preserving and managing the master’s immense artistic legacy in cooperation with the Mitoraj Museum Foundation. The Cricoteka Centre for the Documentation of the Art of Tadeusz Kantor stores records of the artist’s work , which, according to his will, were to be kept constantly in circulation. The archives of the two artists and the art collections they built continue to be the matrix for exhibitions, publications, dialogue with art and research processes. The existing Kantor Museum and the Mitoraj Museum, which is under construction next to the Atelier, seem to be institutions with a very similar mission. They are places where the art and ideas of both artists exist in a continuous process initiated by them, thus remaining truly and vividly present.

Małgorzata Paluch-Cybulska

Referenced materials:

[1] Kantor was given chair of the Department for the period from 1 October 1967 do 30 September 1969, but was dismissed on 30 November 1968.

[2] Igor Mitoraj speaking in the documentary “Tadeusz.kantor@europa.pl”, written and directed by Krzysztof Miklaszewski, produced by Studio Filmowe Kalejdoskop, 2010.

[3] Klein patented his favourite painting colour – ultramarine – as International Klein Blue (IKB).

[4] Costanzo Costantini, „Blask kamienia”, translated by Stanisław Kasprzysiak, Wydawnictwo Literackie 2003, p. 10. [English translation by Robert Gałązka].

[5] Ibidem, p. 13.

[6] Ibidem, p. 27.

[7] Transcript of a fragment of Tomasz Ziółkowski’s programme “Scena kariery” in 2003, in: Agnieszka Stabro, “Igor Mitoraj. Polak o włoskim sercu”, Dom Wydawniczy REBIS, Poznań, 2023, pp. 212-213.

[8] Igor Mitoraj speaking in the documentary „Tadeusz.kantor@europa.pl”, idem.

[9] Costanzo Costantini, op. cit., p. 26.

[10] Ibidem, p. 16.

[11] Ibidem, p. 21.

[12] Ibidem, pp. 18-19.

[13] Ibidem, pp. 21, 75.

[14] Ibidem, p. 17.

[15] The film „Więzy”, directed by Piotr Mikucki, Telewizja Polska SA, 1995. As quoted in: Agnieszka Stabro, op. cit., p. 23.

[16] Tadeusz Kantor, „Moja twórczość, moja podróż”, [as quoted in:] „Pisma”, vol. 1, „Metamorfozy. Teksty o latach 1934–1974”, selected and edited by Krzysztof Pleśniarowicz, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich–Ośrodek Dokumentacji Sztuki Tadeusza Kantora Cricoteka, Wrocław–Kraków 2004–2005, p. 13 [English translation of the quotation by Jessica Taylor-Kucia].

[17] Konstanty Puzyna, „Półmrok. Felietony teatralne i szkice”, Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, Warsaw 1982, p. 111.

[18] Costanzo Costantini, op. cit., pp. 60-61.

[19] Tadeusz Kantor, “Ulisses 1944”, [as quoted in:] Michal Kobialka, “Further On, Nothing: Tadeusz Kantor’s Theatre”, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis 2009, p. 40.

[20] Rafał Solewski, „Dziedzictwo i tożsamość w twórczości Tadeusza Kantora. Wobec postmodernizmu”, in: „Dziś Tadeusz Kantor! Metamorfozy śmierci, pamięci i obecności”, collective publication, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, Kraków 2014, p. 356.

[21] Malcolm Chase and Christopher Shaw. See: Ewa Domańska, „Po-postmodernistyczny romantyzm (Sensitivism – „nowa” folozofia historii – Franklin R. Ankersmit)”.

[22] Costanzo Costantini, op. cit., p. 101.

[23] Packaging objects is typical of American art of the 1960s and 1970s. E.g.: Christo, Cesar, Claes Oldenburg, Edward Kienholz.

[24] H. Belting, “Face and Mask: A Double History”, translated by Thomas S. Hansen and Abby J. Hansen, Princeton University Press, Princeton 2017 p. 27.

[25] Ibidem, p. 25.

[26] When asked in an interview if he has been a model for his sculptures, he said that at least three times: foot, hand and leg. “Rozmowy na nowy wiek – z Igorem Mitorajem o pięknie”, TVP rekonstrukcja, https://cyfrowa.tvp.pl/video/rozmowy-na-nowy-wiek,z-igorem-mitorajem-o-pieknie,35089508

[27] The artist failed twice to enroll in the Faculty of Acting of the Łódź Film School.

[28] Transcript of a fragment of Tomasz Ziółkowski’s programme “Scena kariery”. Idem, p. 215.

[29] Costanzo Costantini, op. cit., p. 77.